You’re ambitious. You’ve done everything “right.”

From the outside, it looks like you’re moving forward, doing well, maybe even thriving. But something inside feels... off. Like you’re living a life that checks all the boxes, but wasn’t written by you.

Eventually, the question creeps in, quiet at first, then louder:

Is this really what I want?

You’re not alone in asking it. Many of us spend years chasing goals we never consciously chose. Goals handed to us by parents, culture, school, or social media.

Not because we’re lost, but because we’ve never been taught to pause and investigate the origins of our desires.

So here’s a truth worth exploring:

The hardest part of building a meaningful life isn’t doing the work.

It’s knowing which work is yours to do.

This article is your guide to figuring that out.

Why You Might Not Know What You Want

We like to think we’re the authors of our own goals. But if you trace your biggest wants, you’ll often find they didn’t begin with you.

You wanted the promotion because your peers celebrated it. You wanted the house because it looked great on someone else’s feed. You wanted the life, not because it was right, but because it looked admired.

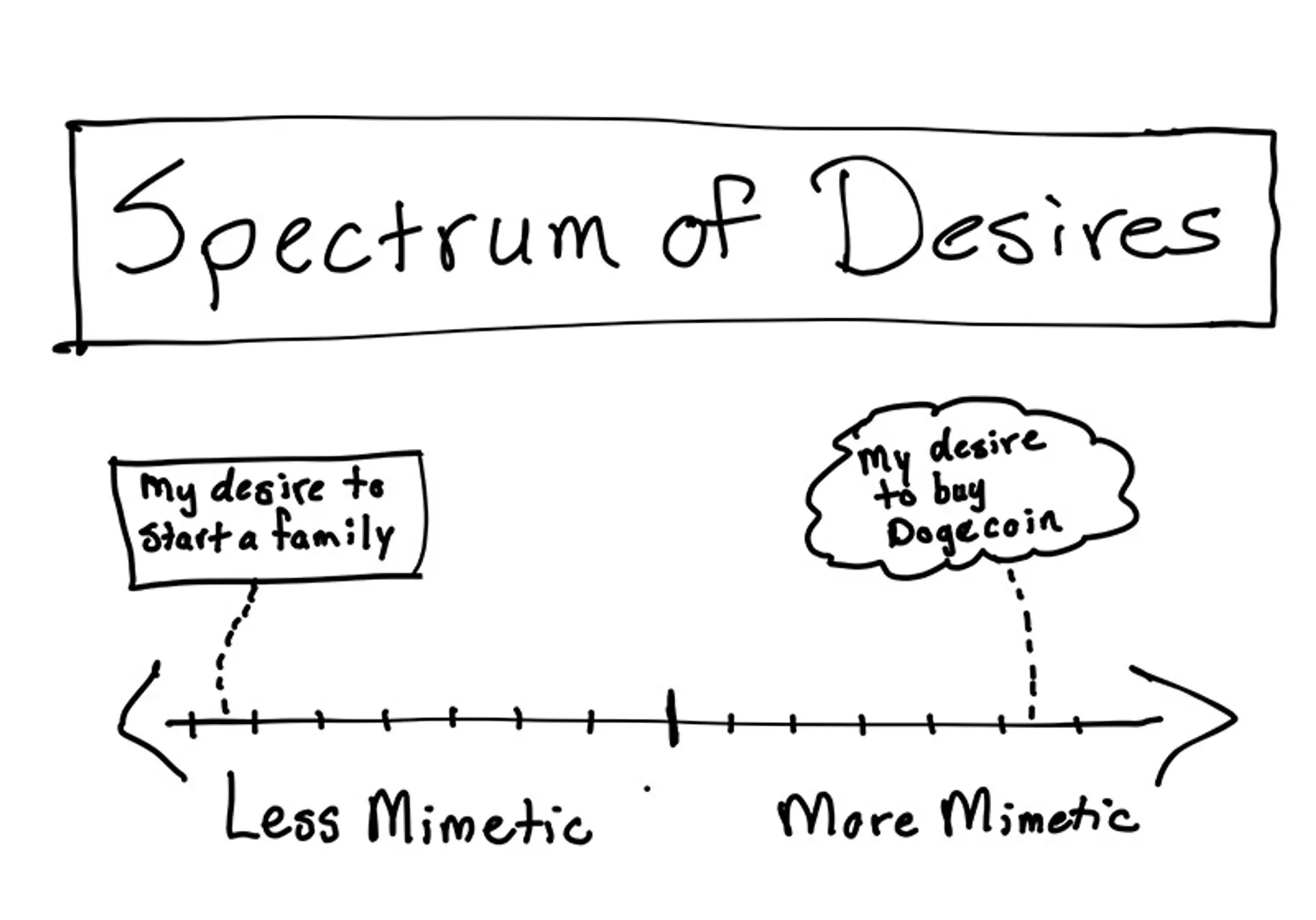

French philosopher René Girard called this phenomenon mimetic desire. It means we don’t generate our wants in isolation, we simply copy them from others.

Girard argued that human beings are inherently imitative creatures, and studies in developmental psychology support this. For instance, infants learn through mimicry long before language develops, and neuroscience research on the mirror neuron system shows that our brains are wired to simulate the actions and emotions of those we observe.

In other words, your desire for a certain lifestyle, partner, or profession may have been modeled to you by someone else, such as a parent, a mentor, a social media influencer, and you subconsciously internalised it as your own.

Understanding this mechanism is step one in freeing yourself from it.

The Difference Between Thick and Thin Desires

Now, not all desires are created equal. Luke Burgis, in his book Wanting, distinguishes between "thin desires" and "thick desires."

- Thin desires are shallow, reactive, and largely mimetic. They rise and fall based on external stimuli and often don’t lead to lasting satisfaction.

- Thick desires, on the other hand, are deeply rooted. They’re shaped by our core values, lived experiences, and sense of purpose. They tend to endure, even as our circumstances change.

But what actually makes a desire 'thick'? What gives it that sense of depth and staying power?

To answer that, we can turn to one of the most well-supported frameworks in motivation science: the Self-Determination Theory.

The Self-Determination Theory

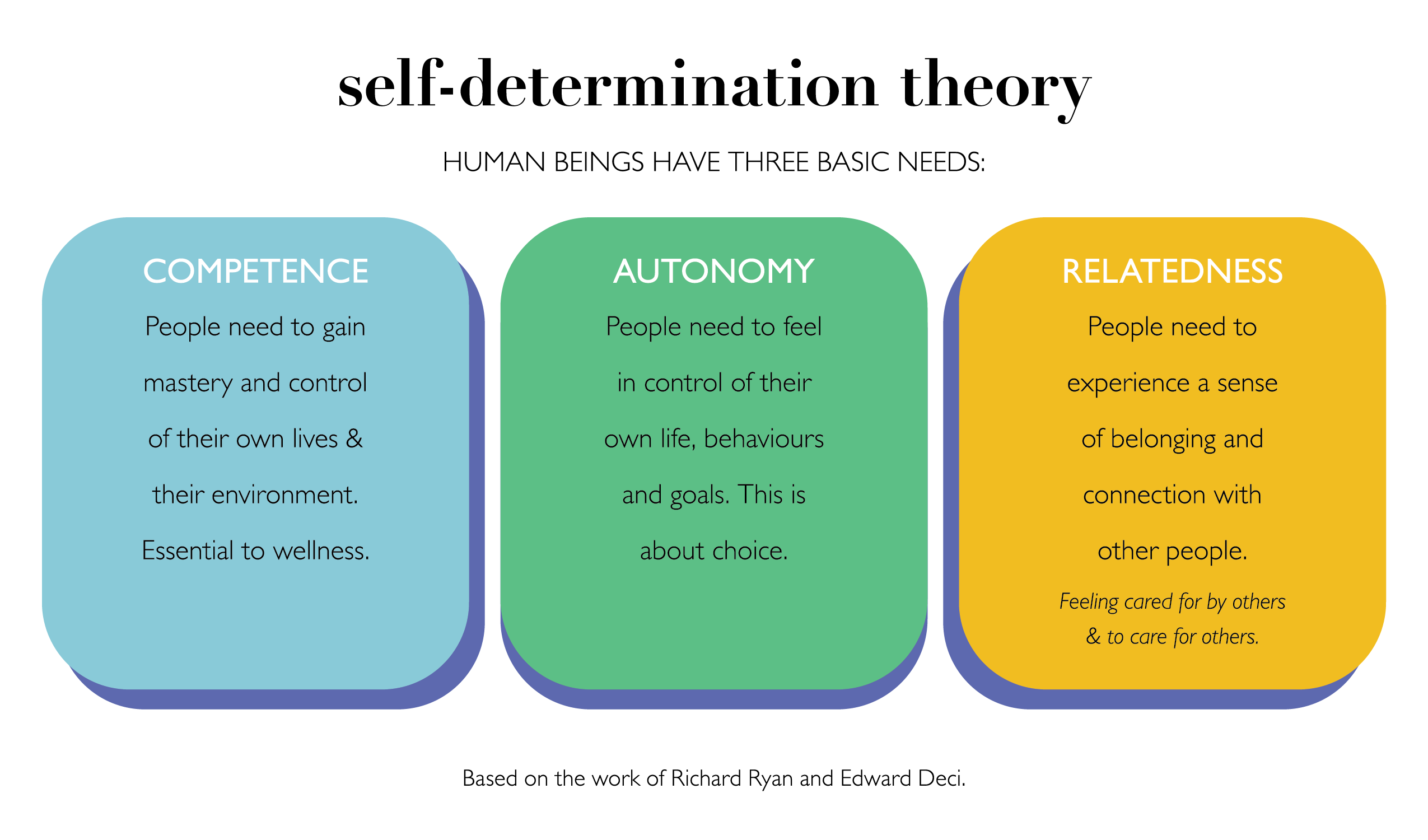

The Self-determination theory, developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, offers one of the most influential and empirically supported frameworks for understanding human motivation. It explains why we feel deeply motivated to pursue some goals and apathetic toward others.

At its core, the self-determination theory proposes that all humans are driven by three universal psychological needs:

- Autonomy: the need to feel like our actions are chosen and self-endorsed. Autonomy doesn’t mean independence; it means owning your choices and feeling aligned with what you’re doing.

- Competence: the need to feel effective in your efforts and to experience mastery over time. This is the innate drive to learn, grow, and improve.

- Relatedness: the need to feel meaningfully connected to others. We thrive when we feel that we belong and are supported by those around us.

When these three needs are satisfied, we’re more likely to feel motivated, fulfilled, and engaged with life. But when they’re thwarted, by environments, relationships, or goals that are misaligned, we struggle.

This ties into a well-known idea in psychology:

- Intrinsic motivation is when you do something because it feels meaningful to you, like learning, creating, helping others, or exploring something you're curious about.

- Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is when you’re driven by rewards or pressure, like money, grades, approval, or social status.

Studies show that intrinsic goals lead to greater happiness, resilience, and long-term satisfaction. They fuel motivation from the inside out. Extrinsic goals might work in the short term, but they often leave people feeling unfulfilled once the reward fades.

That’s why it’s so important to figure out what your "thick desires" are—the goals that reflect your core values and feel true to who you are. These are the goals you’ll stay committed to, even when progress is slow. And they’re the ones most likely to bring real, lasting joy.

So ask yourself: are your current goals helping you grow, feel connected, and stay true to yourself?

Or are you chasing something because you think you should want it?

Five Steps to Clarify What You Truly Want

Gaining clarity on what you truly want isn’t about coming up with the perfect five-year plan. It’s about peeling back the layers of external influence and rediscovering what lights you up at your core.

These five steps are designed to help you move away from reactive, mimetic desires and toward goals that are deeply aligned with your values, your identity, and your unique path.

1. Ask Who, Not What

We often ask ourselves, “What do I want to do with my life?” But a better question to start with is: “Who made me want this?”

To uncover your mimetic desires, start by scanning your current wants. Look at your goals, habits, purchases, and even your opinions. Then ask: Where did this come from?

A helpful method is to list your top 5 current desires and, for each, ask:

- Did I want this before I saw someone else pursue it?

- Would I still want this if no one else did?

This process isn't about judging your desires, it's about becoming more aware of which ones are truly yours, and which ones might be borrowed without conscious thought.

A study from Psychological Science found that people underestimate how much their choices are influenced by others. We like to think we’re making decisions on our own, but we’re often shaped by our environment.

So, in short:

- Write down five things you think you want (e.g., a certain career, a lifestyle, a relationship).

- Next to each one, write who might have influenced that desire.

- And ask: Would I still want this if nobody praised me for it?

2. Categorise Your Models of Desire

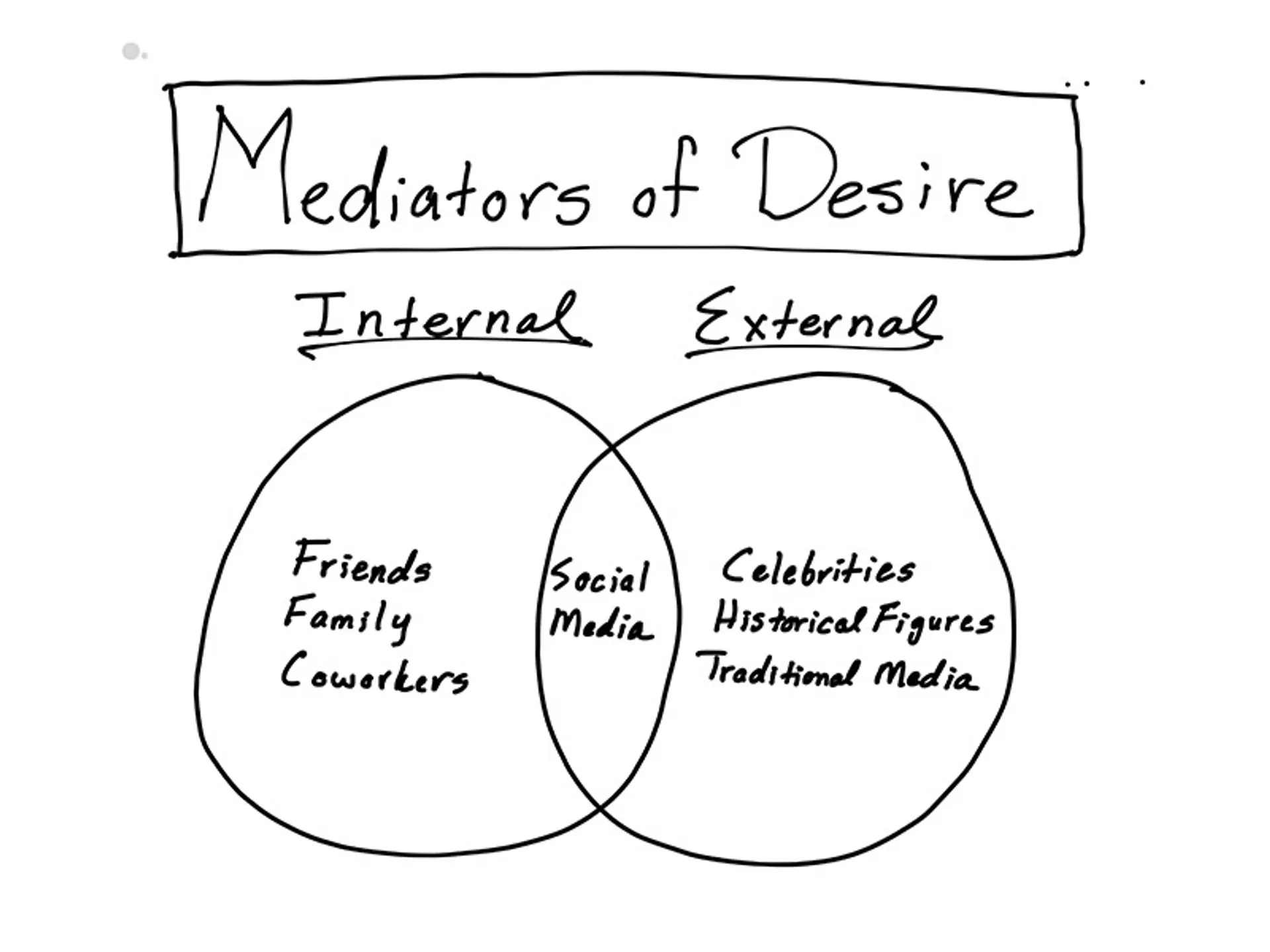

Philosopher René Girard believed that we learn what to want by observing others. These people serve as "models of desire"—they show us what is desirable simply by desiring it themselves. But not all models have the same impact.

Girard identified two key categories:

- Internal models: These are people within your social world such as friends, classmates, colleagues, family members. You see them regularly, interact with them, and compare yourself to them. Because you occupy similar spaces, their desires often feel more relevant and achievable, which can intensify feelings of competition, jealousy, or self-doubt.

- External models: These are people outside your immediate reach, like celebrities, influencers, authors, athletes, or historical figures. You admire them from a distance. Their success may still influence your desires, but you're less likely to feel direct rivalry with them because your lives are so different.

Research backs this up. A 2013 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that close comparisons (like those with peers) are more emotionally intense and damaging than distant ones.

Internal models activate what psychologist Leon Festinger called social comparison processes, where we evaluate our worth based on how we stack up against others like us.

Make this actionable:

- Draw two columns on a page: label one "Internal Models" and the other "External Models."

- List out the people in each category who influence what you want, how you think about success, or how you measure yourself.

- For each person, ask: “Do they lift me up or leave me feeling behind?” “Do I want what they have because it aligns with my values, or just because it seems desirable?”

- If certain models consistently leave you feeling insecure, anxious, or off-track, consider limiting the influence they have, whether that means muting them online or mentally re-framing their significance.

The goal isn’t to cut out all influence, it’s to become more conscious of it, so you can stop copying and start choosing.

3. Map Your Systems of Desire

Most of our desires don’t appear out of thin air, they are shaped by the environments we move through every day. These environments, or systems, send us powerful signals about what matters and what doesn’t. Over time, these signals can shape what we strive for, often without us even noticing.

For example:

- Schools tend to reward academic achievement: good grades, gold stars, and test scores.

- Social media rewards attention: likes, shares, and follower counts.

- Corporate cultures may reward productivity, competition, and career titles.

- Startups often reward long hours, hustle, and rapid growth.

- Families might reward stability, tradition, or making choices that maintain harmony.

These systems don’t just shape behaviour, they shape identity. They subtly teach us what’s worth chasing and who we should become.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called this the habitus, a system of norms and expectations that influences our tastes, goals, and behaviours without us consciously realising it.

The problem is, if you never stop to question the system you’re in, you might spend years chasing a version of success that isn’t even yours.

Make this actionable:

- Reflect on the main systems you belong to: your school, workplace, community, friend group, culture, or online spaces.

- Ask: “What does success look like in this system?” (e.g., being admired, being busy, being rich, being liked?)

- Then ask: “Do I actually care about this version of success, or have I just absorbed it?”

This exercise helps you step back and see the bigger picture. Sometimes, we realise we’re climbing a ladder that’s leaning against the wrong wall. You don’t have to quit everything, but once you see the system, you can stop letting it choose your goals for you.

4. Notice the Feeling of Restlessness

Restlessness isn’t just a mood, it’s a message. It often shows up when something deep inside you knows you’re off course, even if your life looks perfectly fine from the outside. You may be achieving your goals, hitting milestones, and receiving praise, yet still feel a low-grade discomfort, boredom, or emptiness that won’t go away.

Psychologist Dr. Lisa Firestone explains that this kind of discontent often stems from a disconnect between your daily actions and your intrinsic motivation. When we pursue goals that don’t match our deeper values, we might succeed outwardly but feel like we’re going through the motions.

This misalignment can show up as:

- Feeling unmotivated even when you’re "doing well"

- Constantly switching goals or interests without lasting satisfaction

- Chasing accomplishments but never feeling fulfilled when you get them

This isn’t laziness or lack of ambition, it’s a sign that your goals might be thin desires, not the thick ones rooted in your true self.

Make this actionable:

- Journal: When was the last time you felt genuinely energised or excited by what you were doing?

- Notice: What kinds of tasks make you feel drained, bored, or robotic—even when they’re part of your "plan"?

- Highlight: Which moments or activities make you lose track of time, feel deeply engaged, or leave you more energised afterward?

These are clues. They point to the kinds of pursuits that align with your thick desires, goals that connect with who you are at a deeper level, not who you think you’re supposed to be.

5. Become the Author of Your Desires

Just because a goal didn’t originate entirely from within you doesn’t mean it’s invalid. Maybe you first wanted to write a book because your favourite author inspired you. Or maybe you pursued a career because it impressed others. That’s okay. What matters most is what you decide to do with that desire now.

Philosopher Charles Taylor called this process strong evaluation. It means assessing your desires not just by how intense they feel, but by whether they align with your values, your sense of purpose, and the kind of person you want to become. It’s about separating the noise from the signal.

Being the author of your life means taking your raw material, your influences, your environment, even your mimetic desires, and shaping it into something intentional. Instead of living out a script written by others, you rewrite the story in your own voice.

Make this actionable:

- Look at the goals or dreams that feel most important to you right now.

- Ask yourself: “Why do I want this?” Write down your answer. Then ask again: “And why does that matter to me?” Keep going until you hit something meaningful.

- Notice which goals still hold weight even after deeper questioning. These are likely connected to your values, not just validation.

- Choose to commit to these goals, even if they look different from what people around you expect.

When you do this, you’re no longer just reacting to desire, you’re choosing it, shaping it, and taking responsibility for it. That’s what it means to become the author of your life.

Living an Anti-Mimetic Life

To live an anti-mimetic life is to stop copying and start choosing.

It means:

- Choosing depth over distraction.

- Values over validation.

- Self-authorship over social conformity.

It doesn’t mean rejecting ambition or turning away from achievement. It means developing the discernment to know which desires are truly your own—and having the courage to follow them, even when they deviate from the mainstream.

Most people unconsciously absorb the desires of the world around them. Living anti-mimetically means slowing down, paying attention to those influences, and deciding for yourself whether to keep or discard them. It’s about making intentional decisions instead of default ones.

To live this way, you can begin cultivating daily practices that build self-awareness and resilience to social pressure:

- Spend more time offline. Reduce the noise so you can hear your own thoughts.

- Reflect before reacting to trends. Ask if something is truly meaningful to you, or if it’s just popular.

- Choose timeless values over fleeting rewards. Curiosity, growth, service, and creativity never go out of style.

- Create space for solitude and silence. It’s where your real voice tends to speak up.

- Notice when you’re trying to prove something. Often, that’s a sign you’re chasing someone else’s script.

Living this way isn’t always easy. It can mean saying no when others expect yes. It can mean taking a slower path while others sprint. But the result is a life that feels coherent, energising, and yours.

Research in positive psychology supports this. Studies by Kasser & Ryan (1996) show that people who pursue intrinsic goals, like meaning, connection, and personal growth, report higher well-being than those who chase extrinsic rewards like money, fame, or appearance.

You don’t need to abandon the world. But you do need to stop letting it define you. The anti-mimetic life is a return to what you knew before the world told you who to be.

Final Questions to Ask Yourself

Here are a few prompts to go deeper:

- Who are three people who shape my current ambitions?

- What values do I want my goals to reflect?

- What did I love doing before I learned what was "successful"?

- Which goals feel energising, not draining?

- What kind of life would I build if no one was watching?

You don’t need all the answers today. But asking the right questions will change everything.

Why It Matters

If you don’t know what you truly want, someone else will decide for you.

The cost isn’t just time. It’s meaning. Alignment. Joy.

When you understand the source of your desires, you stop drifting. You start designing.

Not just a successful life. A true one.

You don’t have to follow the crowd.

You can follow you.